Crowdsource Creativity

I'm a performer

Where performers get paid to perform

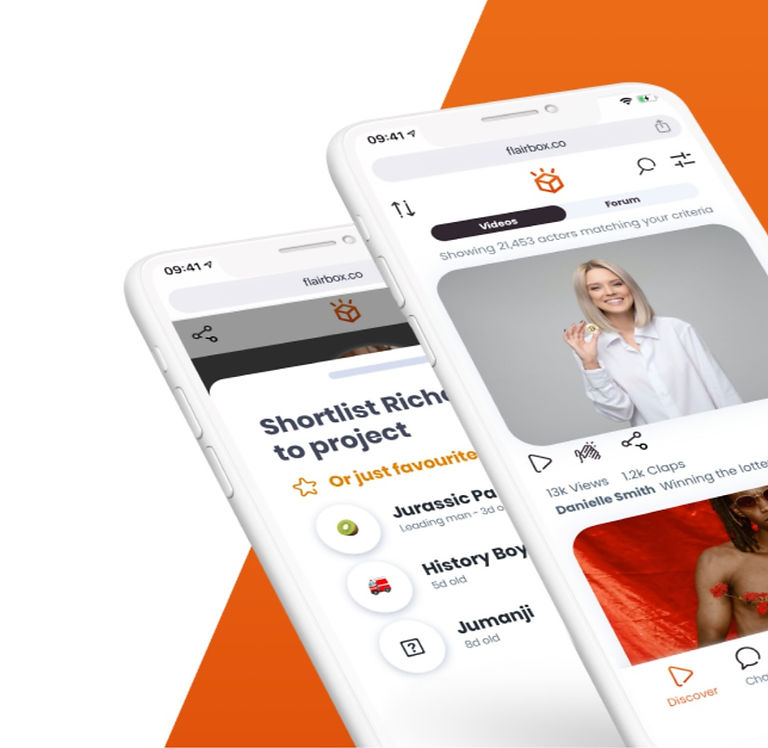

FlairBox is a global community of performers that allows talented individuals to create simple content for brands and get paid for it.

PERFORM

Get paid to perform.

On FlairBox you can make money from your creativity. Simply follow the brief set by a brand, and come up with a video to submit to their competition. Get paid for your content and you can win incredible prizes too.

CONNECT

Meet our global performance community.

The founders of FlairBox (The majority of them have built their careers at VBET) and most of the FlairBox team are also performers, so we know just how lonely the life of a performer can be. That’s why you can connect, message, post on the forum and engage with other performers’ work on the platform. You’re only ever a click away from a global community of performers that are just like you.

BE DISCOVERED

Where talent does the talking.

FlairBox aims to make the performance industry a fairer and more accessible place – where performers feel they belong. Open to all to join, and with a unique algorithm to suggest trending performers at the top of the feed, we’re making this no longer about who you know or what you’ve been in, or your background and connections, but about your talent.

I'm a brand

Crowdsource Creativity

Leverage the power of thousands of performers to create incredible, performer-generated content for your social channels.

The Power of PGC

Consumers find UGC 9.8x more impactful than influencer content when making a purchasing decision (Stackla)

We take UGC one step further, with PGC (Performer-Generated Content). Whether you’re simply looking for content to post on social media or to seed a wider trend for your audience, we guarantee incredible performer-generated content for your brand or launch.

The Power of FlairBox

FlairBox will revolutionise how you engage your audience with incredible PGC content from the world’s top performers.

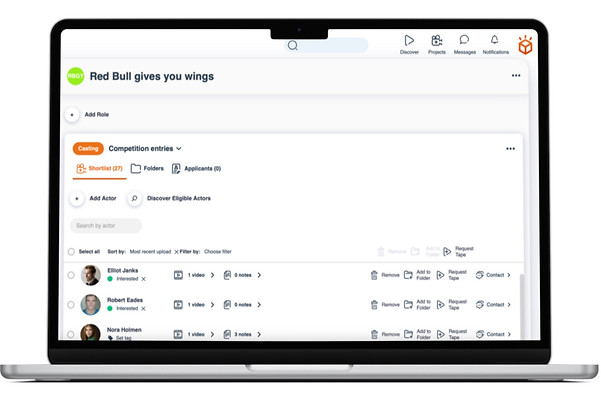

1. Design and implement PGC competitions for your brand.

2. Leverage the power of thousands of performers on FlairBox to guarantee incredible PGC.

3. Seamlessly view and manage submissions through our proprietary video submission software.

4. Choose as many entries as you like - simply to use as assets for your brand, or to seed a wider trend on your socials.

"I think FlairBox is incredible; not just because it’s unique or that it’s easy and simple to use, but because it breaks down the barriers of getting onto a platform that has so many requirements that many actors cannot overcome. FlairBox opens fantastic opportunities up to so many more actors. It’s effective, many people know about it already and in all honesty, I had nothing to lose by signing up!"

Suraj ShahActor Founder of DABB - Diverse Actors Breaking Boundaries

"A platform like FlairBox transforms our lives by having everything in one place. It also means we can view performances from a much wider range of actors at the click of a button, making our job easier, more efficient and exciting.”

Sophie PearsonCasting Associate to Des Hamilton (JoJo Rabbit, The King)

Join the FlairBox Community now!

Already registered? Sign in here or join the community now for free!